The Influence of Mining In Incidents of Lung Silicosis

14

Aug 23

The earliest association of iron-ore mining with life-threatening disease of silicosis dates to over a century. Before that, it was traditionally believed amongst both laymen and the medical professionals, that haematite iron ore mining was a very healthy profession. After the introduction of pneumatic drills is the 19th Century, all the “mishaps” and “evils” that occurred were attributed to their use. Various researchers around the world conducted several studies and inferred that “iron-ore miners not only show a higher mortality from pulmonary diseases but also shown a maximum death rate from phthisis at a later age period” (Craw, 1947). Even today, this statement holds true, and much research has been conducted ever since to understand the mechanism of silicosis and its relation with iron-ore miners.

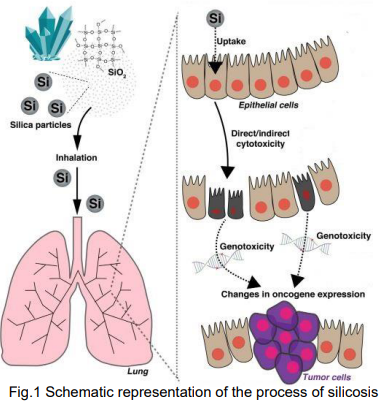

Fig.1 Schematic representation of the process of silicosis

after exposure to silica

(Source: Sato, T., Shimosato, T., & Klinman, D. M. (2018). Silicosis

and lung cancer: current perspectives. Lung Cancer: Targets and

Therapy, 9, 91)

Silicosis is an irreversible and incurable lung disease caused by the inhalation of dust containing crystalline silica particles. Silicosis is one of the most important occupational diseases in the world and exposure to silica generally occurs in mining, construction, works/ quarries, pottery manufacturing and denim sandblasting (Croteau et al., 2004; Ulm et al., 2004; Gungen et al., 2016). Although cement does not contain much silica, substantial amounts of respirable quartz can be generated when concrete building materials containing sand and stone are cut, ground, or drilled. Drilling in confined spaces can cause excessive silica exposure, as reported in hand-dug caissons in Hong Kong (Ng et al., 1987). Workers in the mining industry experience the highest risk of lung cancer due to the magnitude and duration of their silica exposure. Approximately 2 million workers in USA, 2 million workers in Europe, 0.5 million workers in Japan and more than 23 million workers in China are estimated to have been exposed to the causative agent and 4.2% of deaths among industrial workers in China is attributed to silica dust exposure (Leung et al., 2012; Steenland and Ward, 2014; Maciejewska, 2008; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, 2016; Ministry of Health, China, 2011).

Figure 2. Chest radiographs of a patient with silicosis. Simple nodular silicosis (A) and

progressive massive fibrosis (B).

(Source: Leung, C. C., Yu, I. T. S., & Chen, W. (2012). Silicosis. The Lancet, 379(9830), 2008-2018).

Silicosis is a progressive disease characterized by fibrotic changes in the lungs. The sensitivity of chest radiography improves with increasing degree of silicosis.

TREATMENT/PREVENTION OF LUNG SILICOSIS

There is no known cure for silicosis. Supportive therapy involving the prevention of infection, use of bronchodilators and oxygen supplementation are the mainstays of treatment (Leung, 2012). Silicosis patients should generally be removed from further exposure. Job accommodation and personal protective measures are essential for individuals remaining in their jobs, even though these measures cannot fully protect those with proven disease from further damage. Smoking cessation, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are useful in reduction of complications. Empirical treatment with bronchodilators should be considered for symptomatic patients with airflow obstruction. Cough suppressants and mucolytics could be useful for symptomatic relief (Leung et al., 2012). In the past decade, outbreaks of silicosis have been reported in some small-scale companies or mines in developing countries, mainly caused by poor hazard recognition and few protective measures. The initiative is encouraging and supporting countries with silica hazards to establish national action programmes to control silicosis.

Some of the measures as suggested by National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health are described as under:

1. Primary Prevention

- Silica exposure control at source: Substitution of materials; modification of processes and equipment; wet methods; silica warning sign; work practices

- Control silica dust emission or transmission: Isolation of the source or workers; enclosed processes; air curtain; water spray; local exhaust ventilation; general ventilation system; enclosed cabs; air supply system.

- Control silica dust at worker level: Training and education about work practices; personal protection; personal hygiene; personal protective equipment; health promotion.

2. Secondary Prevention

- Surveillance of working environment: Establish concentration of silica dust; assess health risk for workers exposed to silica dust.

- Surveillance of worker health: Periodic health examination, such as chest radiography; early detection of the disease; research into biomarkers for early stages of silicosis

3. Tertiary Prevention: Removal from environment; prevention of complications; modification of work processes; rehabilitation.

References

Cocco, P., Ward, M. H., & Buiatti, E. (1996). Occupational risk factors for gastric cancer: an overview. Epidemiologic reviews, 18(2), 218-234.

Craw, J. (1947). The Control and Elimination of Silicosis in the West Coast Haematite Iron Ore Industry. British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 4(1), 30–47.

Croteau, G. A., Flanagan, M. E., Camp, J. E., & Seixas, N. S. (2004). The efficacy of local exhaust ventilation for controlling dust exposures during concrete surface grinding. Annals of occupational hygiene, 48(6), 509-518.

Güngen, A. C., Aydemir, Y., Çoban, H., Düzenli, H., & Tasdemir, C. (2016). Lung cancer in patients diagnosed with silicosis should be investigated. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports, 18, 93-95.

Leung, C. C., Yu, I. T. S., & Chen, W. (2012). Silicosis. The Lancet, 379(9830), 2008-2018. Steenland, K., & Ward, E. (2014). Silica: a lung carcinogen. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 64(1), 63-69.

Maciejewska, A. (2008). Occupational exposure assessment to crystalline silica dust: Approach in Poland and worldwide. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 21(1), 1.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Pneumoconiosis health management implementation status report in Japan 2016. Tokyo, Japan, 2016.

Ministry of Health C. China’s Health Statistics Yearbook 2011. Beijing,China: Peking Union Medical College Press; 2011.